Sitting on a bench in the heart of the McGill University campus, Farrah says that she and her fellow student protesters want their school to listen. Less than a week ago, students from McGill and other Montreal universities set up dozens of tents on McGill’s campus to denounce Israel’s war on the Gaza Strip, and demand that their universities divest from any firms complicit in Israeli abuses.

They are part of a growing student protest movement that catapulted to international attention last month after demonstrations in the United States last month. The movement shows little sign of slowing down, drawing international headlines as Israel’s Gaza offensive grinds on.

“Campuses from across Montreal have come together for this,” Farrah, who asked to use a pseudonym due to a fear of reprisals, told Al Jazeera. About 75 tents have been erected on a field just a few steps from the university’s main gate in downtown Montreal, Canada’s second-largest city, and a steady stream of supporters arrived throughout the day with supplies and words of encouragement.

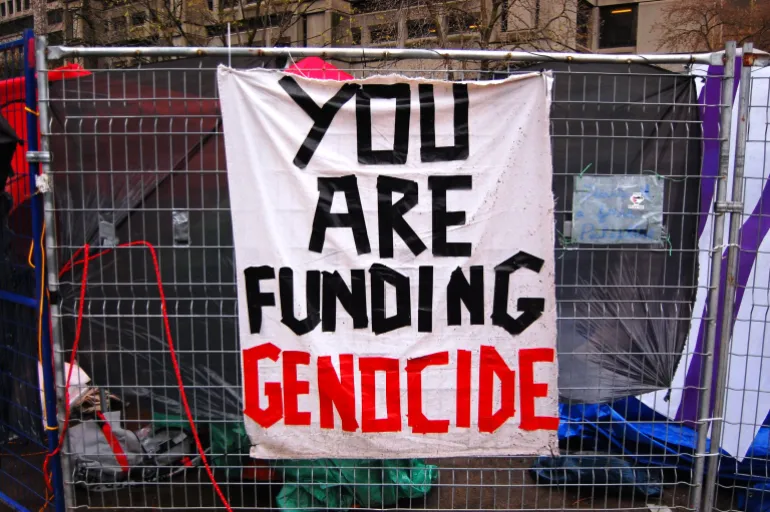

“You are funding genocide,” reads one sign affixed to fencing around the camp, which has been covered in Palestinian flags and large banners. “We will not rest until you divest,” reads another.

“We may be just a group of people, but we understand that we have support and we’re standing in a movement that is all over the world. We’re not the only ones fighting for what’s right,” said Farrah, 21. “These encampments are everywhere.”

Like those in the United States, the encampment at McGill has struck a chord — both with the students and wider community members who support the protesters, and with the pro-Israel politicians and groups that have vehemently denounced them.

Some supporters say the encampments have stirred such strong reactions because they are highlighting stark inconsistencies: governments that say they promote human rights but provide unwavering support to Israel; universities that say they promote freedom of expression but send police to break up peaceful protests; right-wing politicians that denounce liberal “safe space” policies, but are now arguing that pro-Israel students feel unsafe.

The student protests have “exposed a lot of the contradictions in political discourse in the U.S. and by extension, in Canada, too,” said Barry Eidlin, an associate professor of sociology at McGill University. “It hits so close to home for people and [there’s] this sort of hypocrisy between what our governments say they stand for in terms of democracy, human rights, freedom – and the kind of actions that they are supporting” in Gaza, he told Al Jazeera.

The encampments are also highly visible, forcing people to take notice both of the protesters’ demands, as well as the situation in Gaza, where the United Nations’s top court has said Palestinians face a risk of genocide.

“We wouldn’t have started this camp if we didn’t know it was going to have an impact,” said Sasha Robson, a McGill student and member of the university chapter of Independent Jewish Voices, a Jewish group that supports Palestinian rights. “And I think the reason it’s having such an impact is because we are inescapably visible and present. We are holding space on this campus that makes our demand and presence unavoidable,” Robson told Al Jazeera.

But as in the U.S., the McGill encampment and others that have sprung up in other parts of Canada since Saturday have been met with a fierce backlash from pro-Israel groups and politicians.

Just hours after the Montreal camp was established, federal lawmaker Anthony Housefather, one of the most pro-Israel voices in the Canadian parliament, urged the university administration to disperse the protest. “I call upon the McGill administration in public, as I have in private, to make sure that this encampment is removed, according to their own rules, given that we need to make sure that other students feel safe accessing campus,” Housefather said in a video posted on social media.

McGill President Deep Saini said in an email to students and staff on Tuesday that the university had “requested assistance” from Montreal police to remove the encampment. “Having to resort to police authority is a gut-wrenching decision for any university president. It is, by no means, a decision that I take lightly or quickly. In the present circumstances, however, I judged it necessary,” Saini wrote.

On Wednesday, a Quebec judge rejected a separate request for an injunction filed this week on behalf of two McGill students seeking to have the encampment removed. “The balance of inconveniences leans on the side of the demonstrators, whose freedom of expression and of peaceful assembly would be significantly affected” by the injunction, the decision reads. The plaintiffs’s arguments, the judge added, “relate more to subjective fears and discomfort rather than to precise and serious fears for their safety.”

The demonstrators have rejected accusations that their encampment poses a safety threat, and they have noted that it does not block access to the McGill campus or to any buildings. Students have also denied allegations made by the university earlier this week that people at the protest used “antisemitic language” and displayed “intimidating behaviour.”

“We understand the importance of having student support on campus, which is why we chose this location. It’s in a place that has no classes. There [are] no library entrances. It’s not in the way of any walkways or anything,” said Farrah, the 21-year-old McGill student.

Instead, she said the backlash to the encampment reflects the limits that Israel’s supporters in Canada want to place on support for Palestinians. “I think anything – regardless of whether it’s an encampment, a peaceful protest, a children’s storybook – anything at all that has to do with Palestine will hit a nerve with Zionist groups,” she told Al Jazeera. “They just don’t want our voices to be heard.”

That was echoed by Eidlin, the professor at McGill, who said the encampments have spurred “a sense of desperation” among pro-Israel groups in the US and Canada because “they know that they’ve lost the narrative.” “There’s no physical disruption happening; it’s purely the fact that they are making this public statement about needing to put an end to the genocide in Gaza and calling out the universities’s complicity in the genocide that is generating this huge backlash,” he said.

A recent Pew Research Center poll found that 33 percent of Americans between the ages of 18 and 29 said they sympathised more with Palestinians than Israelis – far more than older generations. Only 16 percent of Americans under age 30 said they supported the US government providing more military aid to Israel in its Gaza war. “Amongst young people, this is the issue – and we’ve seen it spread just like wildfire,” Eidlin added.

Michelle Hartman, a McGill professor who supports the encampment, also said the protests have drawn blowback because having so many students of diverse backgrounds speaking out against the Israeli war on Gaza poses a threat to the political status quo.

“People who are going to try to defend [that], and defend occupation and genocide, will find it threatening because the young people are speaking,” Hartman told Al Jazeera of the wave of protests across the US, Canada and other countries.

“It’s really being part of a global movement, and they’re very aware of that, and I think that’s what makes the politicians here scared.”

A member of the activist group Solidarity for Palestinian Human Rights-McGill, who asked that their name not be used due to a fear of reprisals, shared a similar sentiment. “Why is this so upsetting? For sure, it’s the numbers,” the student said. “But you also see that a barrier of fear that our political class and our administrations have been trying to instigate within the broader community … [is] being broken.”

The dire situation in Gaza, where a possible Israeli military ground offensive into the southern city of Rafah has spurred fears of more bloodshed and devastation, has pushed students to take a stand, they told Al Jazeera. “All of this is for Palestine and for Gaza. As the death toll increases and the humanitarian crisis also increases and there’s threats of a ground invasion in Rafah that loom, this is something that has been driving the student body – and this is why students are not afraid,” the student said. “It’s so much greater than just an encampment.